1.4. El producto vectorial#

En esta sección vamos a aprender a manejar el producto vectorial, una aplicación que, dados dos vectores no nulos en \(\mathbb{R}^3\), nos permite calcular un tercer vector ortogonal a los dos dados.

1.4.1. Producto vectorial. Definición y propiedades#

Definition (Producto vectorial)

Sean \(\mathbf{u}=\left( u_{1}, u_{2}, u_{3} \right) = u_{1}\mathbf{i} + u_{2}\mathbf{j} + u_{3}\mathbf{k}\) y \(\mathbf{v}=\left( v_{1}, v_{2}, v_{3} \right) = v_{1}\mathbf{i} + v_{2}\mathbf{j} + v_{3}\mathbf{k}\) dos vectores no nulos. Definimos su producto vectorial como el vector

Suele representarse, aprovechando la notación de determinantes, y desarrollando por los menores de la primera fila,

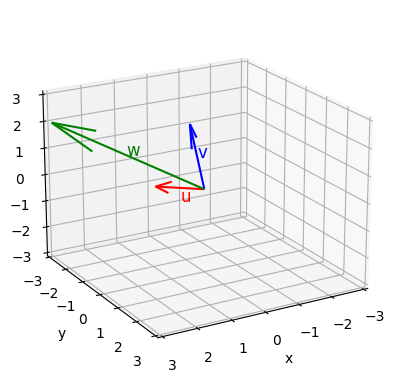

Veamos un ejemplo, aprovechando la función np.cross de Numpy, que calcula directamente el producto vectorial:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib as mp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Definimos los vectores u y v

u = np.array([2, 1, 1])

v = np.array([1, 1, 3])

# Calculamos su producto vectorial con la función, de Numpy, np.cross

w = np.cross(u,v)

display(w)

# Inicialización de la representación 3D

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Representación de los vectores

ax.quiver([0], [0], [0], np.array([u[0], v[0], w[0]]), np.array([u[1], v[1], w[1]]),

np.array([u[2], v[2], w[2]]), color=['r','b','g','r','r','b','b','g','g'])

# Añadimos etiquetas a los vectores

ax.text(u[0]/2, u[1]/2, u[2]/2-0.5, 'u', fontsize=12, color='r')

ax.text(v[0]/2, v[1]/2, v[2]/2, 'v', fontsize=12, color='b')

ax.text(w[0]/2, w[1]/2, w[2]/2, 'w', fontsize=12, color='g')

# Ajuste de los límites de los ejes

ax.set_xlim([-3,3])

ax.set_ylim([-3,3])

ax.set_zlim([-3,3])

# Etiquetas de los ejes

ax.set_xlabel('x')

ax.set_ylabel('y')

ax.set_zlabel('z')

# Orientamos los ejes

ax.azim = 60

ax.elev = 20

plt.show()

array([ 2, -5, 1])

Veamos a continuación algunas propiedades del producto vectorial:

Property (Propiedades algebraicas del producto vectorial)

Sean \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v}\) y \(\mathbf{w} \in\mathbb{R}^{3}\) y sea \(c\in\mathbb{R}\). Se cumple

\(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v} = -\left( \mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{u} \right)\) (anticonmutativa).

\(\mathbf{u}\times\left( \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w} \right) = \left(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\right) + \left(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{w}\right)\) (distributiva respecto a la suma).

\(c \left( \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v} \right) = \left(c \mathbf{u}\right) \times \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{u} \times \left(c \mathbf{v}\right)\).

\(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0} \times \mathbf{u} = \mathbf{0}\).

\(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{u} = \mathbf{0}\).

\(\mathbf{u}\cdot\left( \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{w} \right) = \left( \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v} \right) \cdot \mathbf{w}\).

Property (Propiedades geométricas del producto vectorial)

Sean \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v} \in\mathbb{R}^{3}\) vectores distintos de \(\mathbf{0}\) y sea \(\theta\) el ángulo entre ellos. Se cumple

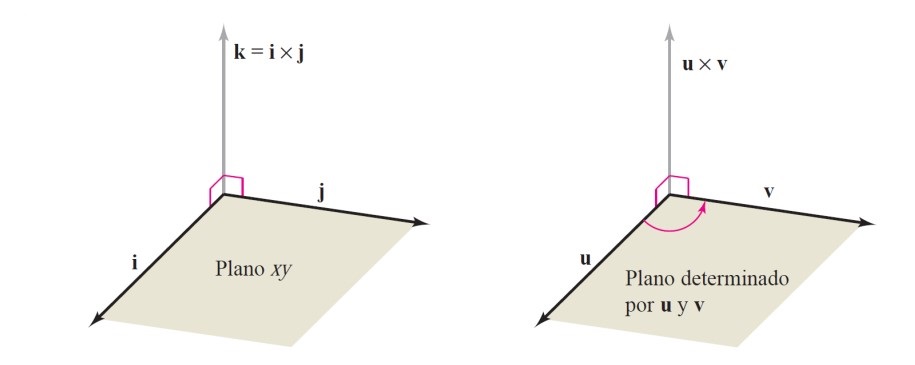

\(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\) es ortogonal tanto a \(\mathbf{u}\) como a \(\mathbf{v}\).

\(\| \mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v} \| = \| \mathbf{u} \| \| \mathbf{v} \| \sin\theta\).

\( \mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0}\) si y sólo si \(\mathbf{u}\) y \(\mathbf{v}\) son paralelos (es decir, si \(\exists c\in\mathbb{R}\) tal que \(\mathbf{v} = c \mathbf{u}\)).

\(\| \mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v} \|\) es igual al área del paralelogramo que tiene a \(\mathbf{u}\) y a \(\mathbf{v}\) como lados adyacentes.

Para ver la orientación de \(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\) se puede utilizar la regla del sacacorchos entre \(\mathbf{u}\) y \(\mathbf{v}\), como se muestra en la siguiente figura: